13-Year-Old Boy Sees Doctor for Hair Loss, Six Months of Treatment Shows No Results, Finally Discovers He Needs a Psychological Consultation

Recently, I saw a patient in the clinic that reminded me of a case from earlier this year. A good friend from my hometown sent me a photo of a 13-year-old boy. He was constantly losing hair on his head. According to his family, they had taken him to numerous hospitals and consulted many doctors for over half a year, but they couldn't find the cause. They tried treatments, but there was no significant improvement. The parents were extremely anxious and eventually went through several contacts to have the photo sent to me, asking for my opinion on what was going on.

When I first saw the photo, I was quite surprised because the pattern of hair loss was very unusual and symmetrical. At first glance, it looked like the M-shaped hair loss pattern seen in androgenetic alopecia. However, upon closer inspection, it was completely different, especially considering this was a 13-year-old boy. How could he possibly have androgenetic alopecia?

This type of hair loss looks as if someone had shaved it with clippers, with very clear boundaries, and you can see hair stubble of varying lengths in the bald area.

I looked at the photo, pondered for a while, and tentatively asked, "Has the child been feeling quite anxious lately?"

Yes, I began to suspect a condition called "trichotillomania," a special type of hair loss related to psychological disorders.

I had heard of some cases before—when children develop psychological issues, they may consciously or unconsciously pull out hair from specific areas of their scalp to relieve anxiety. Over time, this leads to various strange-looking bald patches on the head, which could be mistaken for alopecia areata, tinea capitis, or even androgenic alopecia.

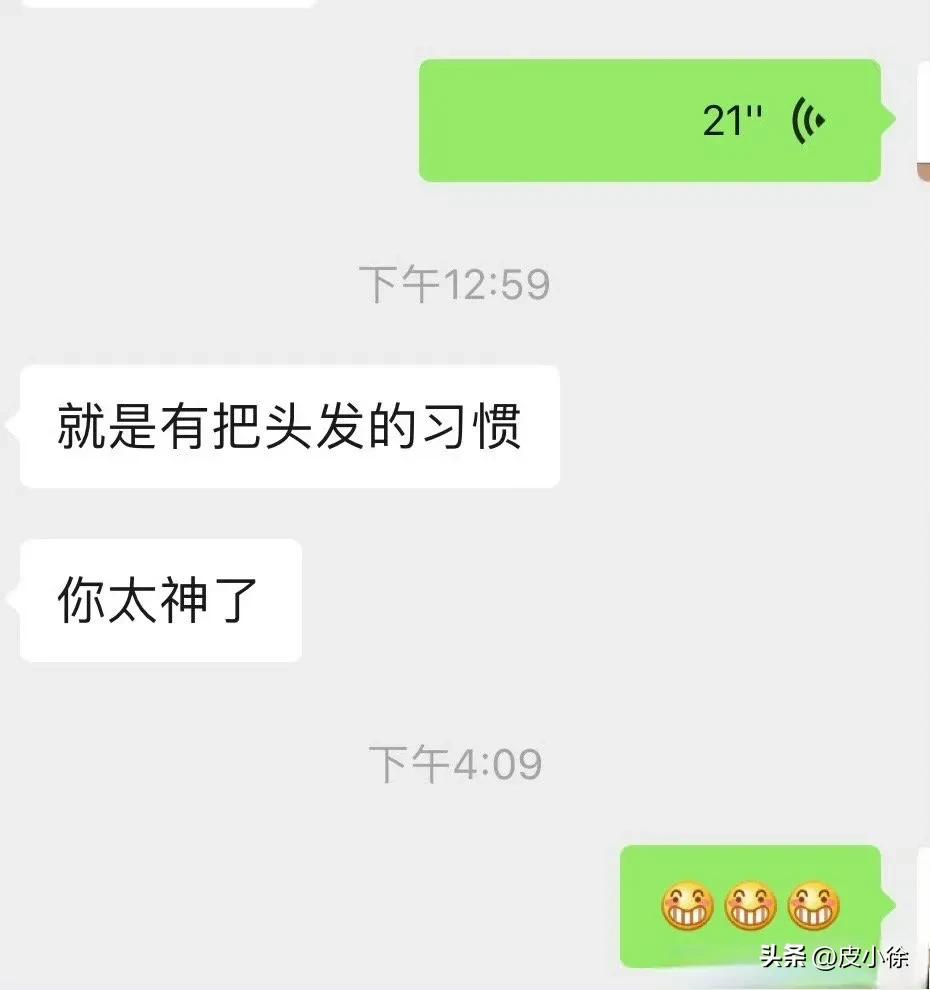

At my suggestion, my friend told the parents about my advice. The parents then realized their child had this habit of pulling out hair. After having a good conversation with the child, they took him to the hospital's psychological counseling department to seek help from a psychologist.

I heard that after more than six months of psychological treatment, the child's hair grew back completely, and his behavior improved in other ways as well.

My friend conveyed the parents' gratitude to me.

Sometimes, children won't voluntarily admit to having this hair-pulling habit, so parents need to carefully observe their children's behavior. Dermatologists diagnose based on irregularly broken hair and use trichoscopy to confirm the diagnosis. Trichotillomania is easy to diagnose, but curing it can be somewhat difficult. After all, psychological issues need to be addressed at a psychological level, requiring comprehensive solutions from parents, society, and even psychologists.

I gave my patient in the clinic some patient advice, hoping he would take it.

Trichotillomania affects not only children but also adults. Psychological counseling is essential, and seeking help from a psychiatrist when necessary is very important. Of course, if you have any related skin issues, I’d be happy to help—whether in person at the hospital or online for those who can’t make it.