The Crisis of Older Adults: How Polypharmacy Accelerates the Aging Process?

Drugs are meant to be weapons against disease, but when medicine cabinets become dazzlingly full, health may instead drift farther away.

Data show that among the 46 million elderly beneficiaries of the U.S. federal Medicare program, one in six is taking eight or more prescription medications concurrently for at least 90 days, totaling over 7.6 million people. Even more startling, nearly 420,000 of them take more than 15 medications daily.

。

In our country, the situation is equally grim. Elderly people over 60 years old have an average of 3.5 chronic diseases and take an average of 4.5 medications per day, and adverse reactions caused by inappropriate medication occur at a rate 2–3 times that of the general population.

An Old Age Surrounded by Medications

Among our country's elderly over 60, more than 70% are on multiple medications, taking at least 9 different types of drugs per day on average, and in severe cases even up to 36 medications daily.

What is even more alarming is that when taking 5 drugs concurrently, the incidence of adverse reactions is 13%; when taking 8 or more drugs, this figure soars to 82%.

As the number of medications increases, the occurrence of drug–drug interactions grows exponentially. When taking more than 5 drugs, the potential drug–drug interaction rate rises to 54%; if 8 drugs are taken simultaneously, drug–drug interactions reach as high as 100%.

The Story of 83-year-old Barbara

Barbara, 83, still looks active: she helps out weekly at the neighborhood shop and finds time to make handmade cards for her grandchildren. But behind years of seemingly proactive treatment, she has been prescribed a long list of medications by various specialists for osteoporosis, chronic back pain, arthritis, and sleep problems.

Many of these drugs appear on the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria as medications that older adults should avoid or use with caution, especially benzodiazepine sedatives, first-generation antihistamines, and muscle relaxants.

As the sedative medications accumulated, Barbara began to fall frequently: tripping at home leading to a hip fracture, injuring herself on an escalator at work, even falling from a ladder and losing consciousness. Her family consistently blamed the home environment or fatigue, but no one suspected the medication list she followed so rigorously every day.

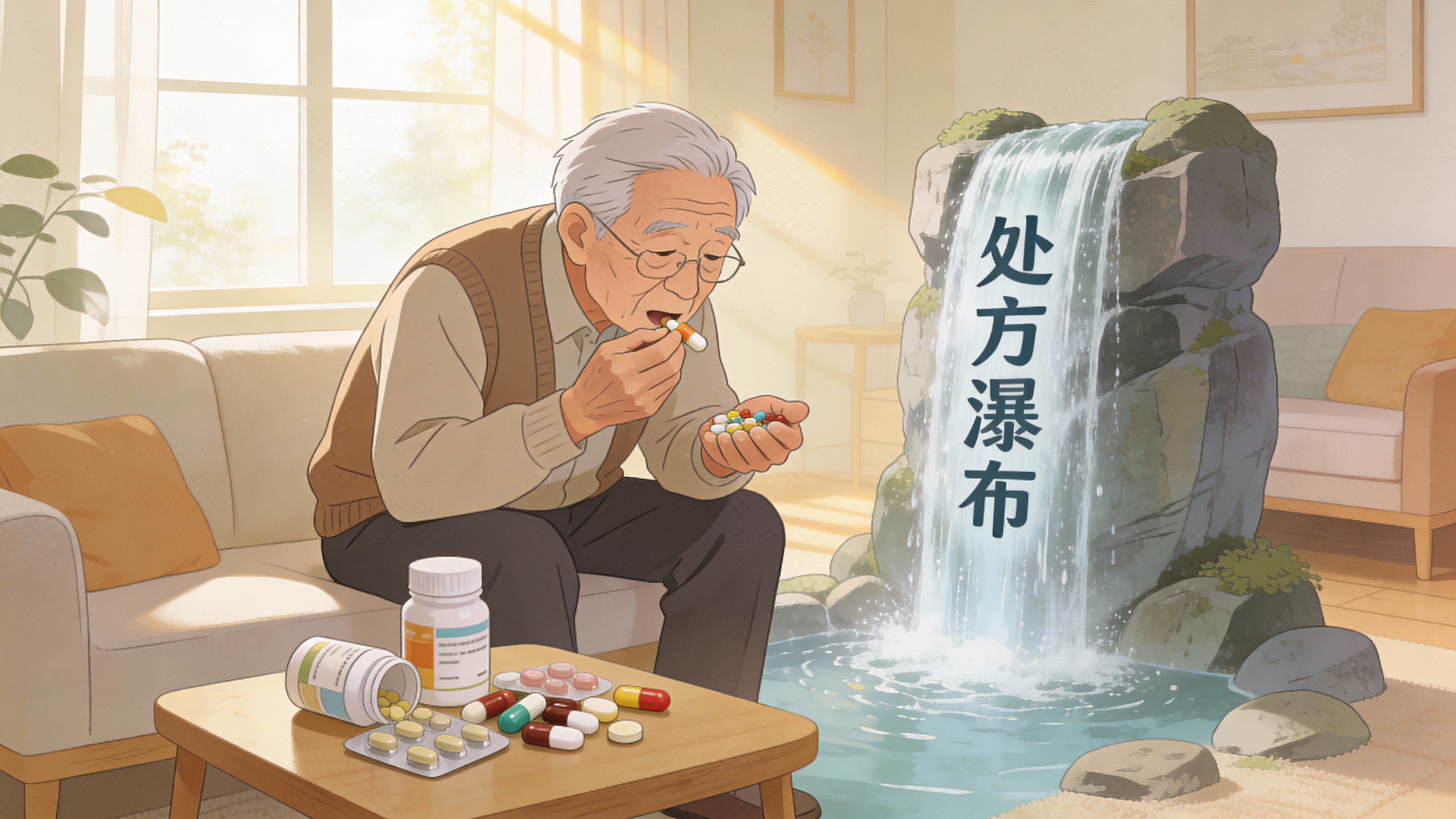

The Vicious Cycle of Medication Accumulation

Polypharmacy significantly increases the risk of adverse reactions. Among causes of death in hospitalized patients, adverse drug reactions due to multiple medications rank third.

Elderly people experience a decline in physiological function: hepatic blood flow is reduced by 40%–50% compared with their younger years, and glomerular filtration rate decreases by 30%–40%, resulting in a marked reduction in drug metabolic capacity. Data show that the proportion of people aged over 65 hospitalized for drug-induced liver injury is seven times that of those under 40.

A more insidious phenomenon is the "prescription cascade" — adverse drug reactions are mistaken for newly emerging diseases, prompting the prescription of additional medications and leading to progressively increasing polypharmacy.

From "polypharmacy" to "precision prescribing"

Barbara is fortunate. After her geriatrician and pharmacist reviewed her medications together, they determined that the additive sedative effects of hydroxyzine, mesoridazine, and gabapentin were the key precipitating factors for her frequent falls. After these drugs were gradually tapered and discontinued stepwise, and her exercise, nutrition, and brain-health rehabilitation were increased, she stopped falling and her mental clarity improved significantly.

This intervention is medically referred to as "deprescribing," meaning the process of safely reducing potentially inappropriate medications under physician supervision.

China's "Standards for Elderly Health Management (2025 edition)" also emphasizes that older adults should undergo regular comprehensive assessments and have their medication regimens simplified.

Prevention and Action Guide: Building a Defensive Barrier for Medication Safety in Older Adults

For families, help the elderly create a medication list including generic names, dosages, and dosing times. Bring all medication boxes or photos to appointments to help clinicians quickly identify potential interactions.

Conduct a "medication checkup" every 3–6 months, with a physician or pharmacist reviewing the regimen. Be alert to high‑risk drug combinations; for example, concomitant use of sedatives and antihypertensives may increase fall risk.

For the healthcare system, promote "pharmacist outpatient clinics" and "medication reconciliation" services to screen for duplicate therapies and contraindicated combinations. Encourage use of assistive tools such as smart pillboxes to reduce missed or incorrect dosing.

Health insurance policy should shift from simple reimbursement to guiding appropriate medication use, avoiding the misconception that reimbursement justifies taking more drugs.

。”

As a Boston University medical professor put it: "For older adults, the more medications they take, the greater the risk. Often, the best treatment is not to add more drugs, but to stop those that shouldn't be taken."

Medications are tools for maintaining health, but more is never better. Precision in prescribing and regular evaluations are the key to preventing elderly people from being overwhelmed by polypharmacy.