Vaginally delivered babies have lower allergy rates than cesarean-delivered babies? The truth is

The mode of delivery experienced at birth indeed significantly affects the establishment of an infant’s immune system. Vaginally delivered infants are exposed to the maternal microbiota during passage through the birth canal; these microbes colonize the gut and help construct the foundational architecture of the immune system. Infants delivered by cesarean section miss this critical microbial transmission, resulting in differences in the initial gut microbiome composition. These differences increase the risk of allergic diseases later in life for cesarean-delivered infants, but they are not irreversible. With scientific postnatal interventions, cesarean-delivered infants can also develop a healthy immune system.

1. Principles of establishment of the infant immune system

The development of an infant’s immune system is a complex biological process. In the maternal uterus, the fetal immune system is in a relatively closed state and relies mainly on maternal immune protection. After birth, the infant begins to be exposed to the external environment, and the immune system is activated and matures. The gut is an important component of the infant immune system; about 70% of immune cells are located in the gut, and there is a close interaction between the gut microbiota and the immune system.

The development of an infant’s immune system can be divided into two stages: innate immunity and adaptive immunity. The innate immune system is the first line of defense present at birth, including the skin barrier, mucosal barriers, and phagocytic cells. The adaptive immune system must be progressively established after birth and includes specific immune cells such as T cells and B cells, which can recognize and remember specific pathogens.

The influence of the gut microbiota on the immune system is mainly manifested in three aspects: first, the microbiota regulates gut barrier function through metabolic products (such as short-chain fatty acids); second, the microbiota activates innate immune responses via pattern recognition receptors (such as TLRs); and third, the microbiota affects adaptive immune responses by modulating the direction of T cell differentiation (such as Th1, Th2, Treg). These interactions together shape the infant’s immune system and determine its response capability to pathogens and allergens.

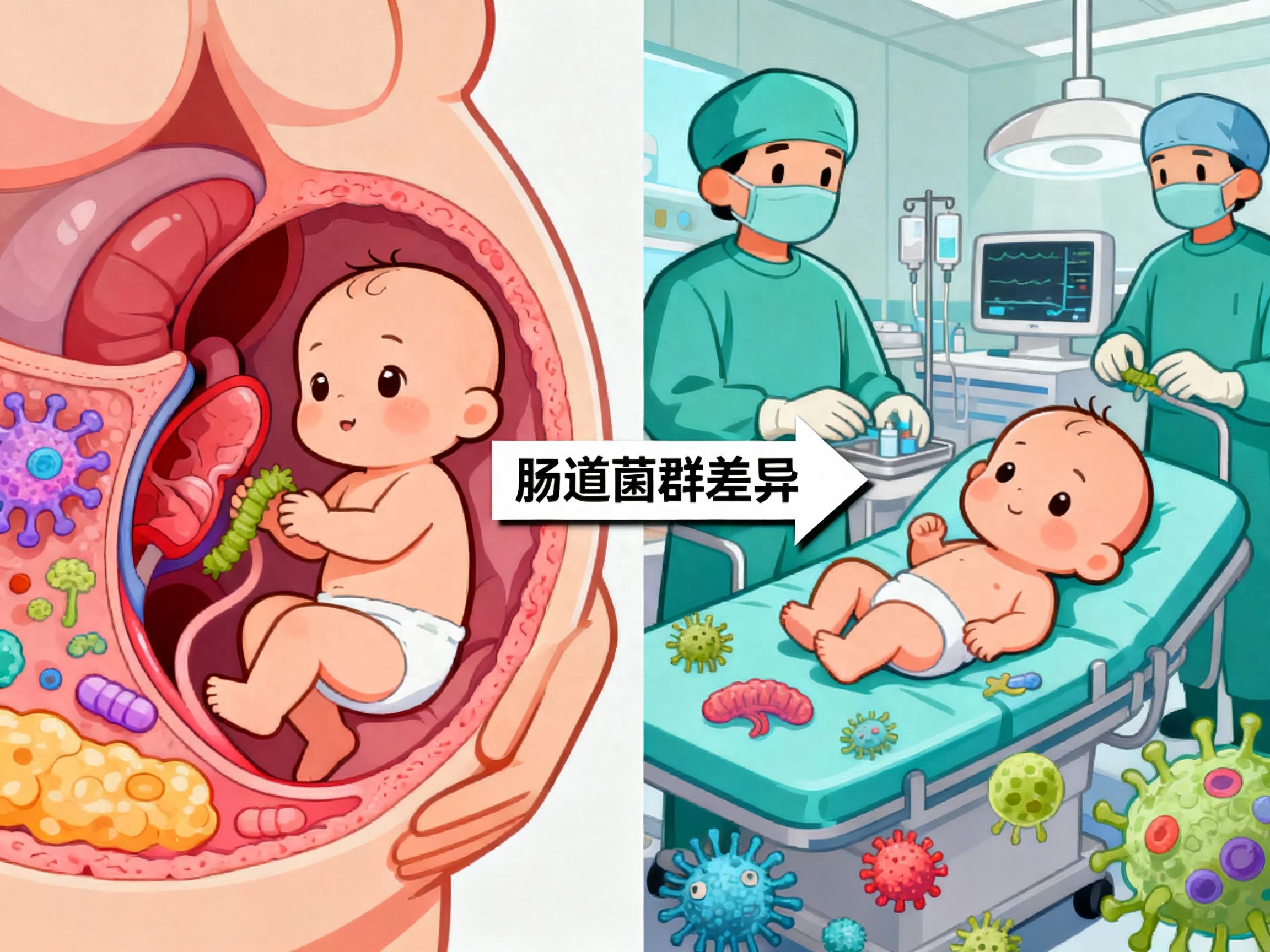

2. Differences in gut microbiota between vaginally delivered and cesarean-delivered infants

The differences in gut microbiota between vaginally delivered and cesarean-delivered infants are mainly manifested in three aspects: sources of microbiota, types, and colonization speed.

Vaginally delivered infants are exposed to their mother's vaginal and intestinal microbiota while passing through the birth canal; these microbes mainly include anaerobes such as Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Bacteroides. Studies show that vaginally delivered infants can establish a relatively stable gut microbiota at about one month after birth, dominated by Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, which can lower intestinal pH by producing organic acids (such as lactic acid and acetic acid), creating an environment unfavorable to the growth of pathogenic bacteria.

Cesarean-delivered infants are mainly exposed to microbes from the operating room environment, healthcare personnel, and the mother's skin surface, such as aerobes including Staphylococcus, Klebsiella, and Enterobacter. The establishment of gut microbiota in these infants is significantly delayed, usually requiring more than 6 months to form a microbiota structure similar to that of vaginally delivered infants. Even during childhood, the gut microbiota of cesarean-delivered infants still differs from that of vaginally delivered infants, characterized by lower abundance and diversity of Bacteroidetes and relatively higher diversity within Firmicutes.

Differences in the types of microbiota directly affect the infant immune system’s "first lesson." Probiotics in the gut of vaginally delivered infants, such as Bifidobacterium, can modulate the immune system through multiple mechanisms, including promoting differentiation of regulatory T cells (Treg), suppressing production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-13), and enhancing intestinal barrier function. Microorganisms found in the gut of cesarean-delivered infants, such as Staphylococcus, may provoke different immune responses and increase the risk of allergies.