Invisible Sound Waves, Visible Lungs | Health Check-up

The lungs are a pair of "bellows" in our bodies that work tirelessly day and night, hidden deep in the chest, invisible and intangible, yet crucial to the quality of every breath. How do doctors "see" the state of the lungs? There are several examination methods, but each has its "shortcomings": X-rays involve radiation, CT scans are not portable, and stethoscopes rely on the doctor's experience... Today, we introduce a safe and convenient "X-ray vision" — lung ultrasound. This "sound wave probe" is becoming a new window for observing lung function due to its advantages of being radiation-free, real-time dynamic, and bedside accessible. It leaves no trace but can capture subtle changes in the lungs.

How does ultrasound "see" the lungs

To understand lung ultrasound, everyone must first grasp a core principle: Ultrasound imaging relies on "echoes."

We can imagine the ultrasound probe as a "sound wave megaphone." It emits high-frequency sound waves inaudible to the human ear. These sound waves travel through the skin and muscles, encountering the body's tissues and organs. Some of the waves are absorbed, while others bounce back. The probe then receives these returning waves, and the computer constructs a dynamic black-and-white image on the screen based on the intensity, time, and direction of the echoes.

However, the lungs differ from solid organs like the liver and kidneys, which are filled with gas. Air is ultrasound's "nemesis"—most of the sound waves hitting the air in the lungs are reflected back, preventing them from penetrating deeply. It's like tapping a balloon filled with air—you can hear a clear echo but cannot discern its interior. Therefore, ultrasound was once thought to be "impenetrable" when it came to the lungs. But later, people discovered that when alveoli are filled with inflammatory fluid (consolidation), lung tissue collapses (atelectasis), or there is fluid accumulation in the pleural cavity, the gas in the affected areas is replaced by liquid or consolidated tissue. This allows the sound waves that were previously blocked by lung gas to penetrate the abnormal areas, clearly displaying their internal structures. These "boundary signals" generated by the lesions form the cornerstone of lung ultrasound diagnosis.

It must be emphasized that lung ultrasound cannot directly observe healthy, air-filled lung tissue. Instead, it assesses dynamic changes at the lung-wall interface by analyzing specific "artifacts" like the pleural line and A-line. Additionally, it differs from routine chest ultrasound. Chest ultrasound is a broader concept that encompasses all structures within and around the chest, including the chest wall, ribs, lungs, pleura, and heart. In contrast, lung ultrasound focuses specifically on the assessment of the lungs, pleura, and respiratory muscles, making it a highly targeted and important branch of chest ultrasound.

Who needs a lung ultrasound

While lung ultrasound is good, it's not necessary for everyone to have routine checks. It's more like a "scout's" gun, only useful in specific situations. The following groups are particularly suitable for lung ultrasound.

Emergency and critically ill patients: Those with sudden difficulty breathing, chest pain, or trauma, as doctors can quickly determine if they have pneumothorax, pleural effusion, or pulmonary edema through lung ultrasound.

Postoperative or long-term bedridden patients: Helps to detect occult pneumonia, atelectasis, or thromboembolism-related lung changes.

Heart failure or kidney failure patients: Monitor for pulmonary edema and its severity.

Children and pregnant women: Non-radiation, can be repeatedly evaluated for lung conditions.

Unexplained fever or high infection indicators: Assist in diagnosing pneumonia, pleurisy.

What preparations are needed before the examination

Preparation before the examination is very simple. The examinee needs to wear loose clothing, cooperate with the doctor to adjust the sitting or lying position, and breathe calmly. There is no need for fasting, no need for contrast agent injection, and almost no contraindications.

Does ultrasound worsen lung disease

This is the most concerned question for the examinee. The answer is very clear: lung ultrasound will not worsen lung disease; it is more like a "gentle scout" that transmits information with sound waves without leaving any "trace." Medical diagnostic ultrasound has extremely low energy and contains no radiation at all—it does not rely on "emitting" harmful substances but rather on receiving echoes of sound waves reflected by human tissue to create images, just like "listening to echoes with ears."

Currently, there is no medical evidence to suggest that properly performed lung ultrasound has any adverse effects on lung diseases such as pneumonia, pneumothorax, or pulmonary edema, nor does it damage lung tissue or interfere with respiratory function. On the contrary, it can be safely used repeatedly: whether for critically ill patients who need dynamic monitoring or for children and pregnant women who are sensitive to radiation, ultrasound examinations can be performed with peace of mind.

What can be seen in lung ultrasound images

Scene 1: "Coastline and Waves" - Pleural Line and A Line

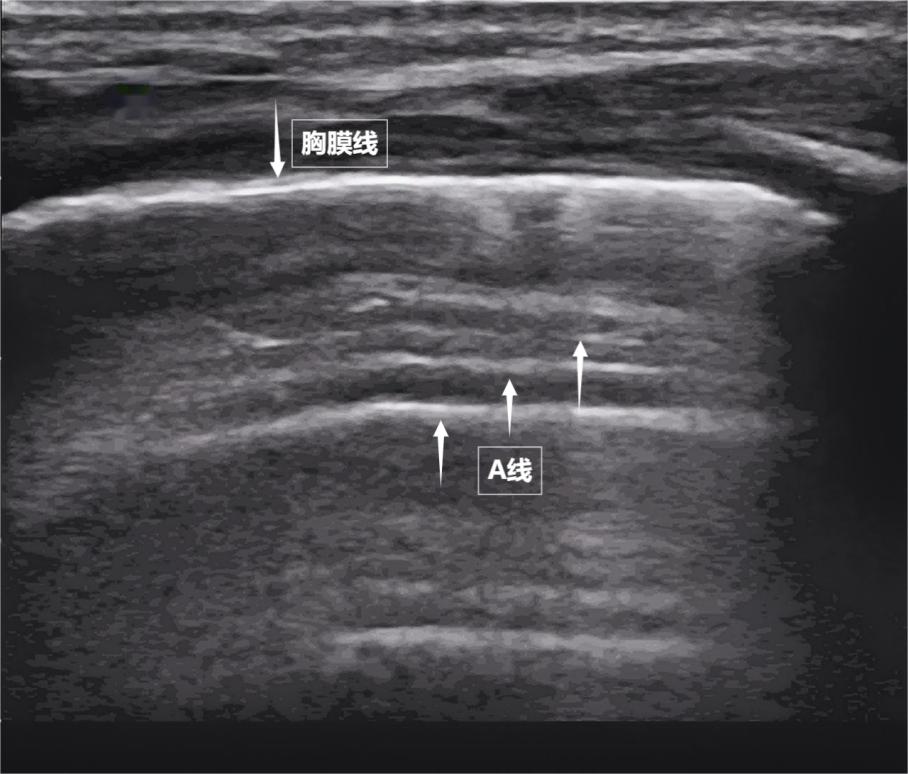

When the sound wave passes through the gaps between the ribs of the chest wall, it first encounters a smooth film closely attached to the surface of the lungs—the parietal pleura and visceral pleura. They are tightly adjacent to each other, with no excess gas or fluid in between. On the screen, they appear as a bright, smooth horizontal line, together forming the pleural line. This line is the "coastline" of the lungs. Below it, due to the strong reflection of sound waves by the large amount of gas in the alveoli, a series of bright, parallel lines appear on the screen, equally spaced and repeatedly appearing, extending continuously into the depth of the screen like waves—this is the A line (see the following image). The A line is a typical sign of a normally aerated lung. Its presence directly indicates that the lung surface is well-aerated and that there is no abnormal accumulation of fluid or gas in the pleural cavity.

Figure shows the ultrasound appearance of a normal newborn's lungs

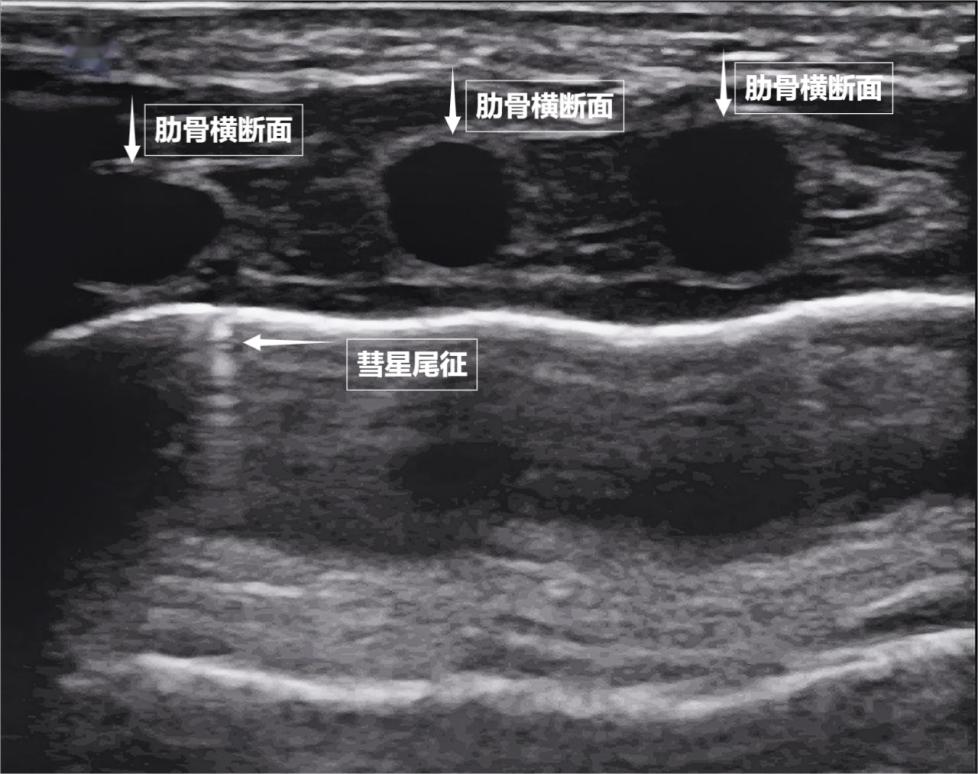

Second Scene: "Beach and Waves" - Lung Sliding Sign

If we switch the ultrasound image to real-time dynamic mode, transforming a "photo" into a "movie," a more magical scene appears. As we breathe, the pleural line gently slides with the movement of the chest wall—this is the "lung sliding sign." It indicates that the lungs are closely attached to the chest wall, allowing for free and smooth breathing. If there is a pneumothorax or pleural effusion between the lungs and chest wall, this sliding disappears. Sometimes, tiny bright white flickering spots may also appear below the pleural line, known as the "comet tail sign" (see below). When they appear in small, isolated quantities, they are usually reflections of normal lung interlobular septa and are nothing to worry about.

Scene Three: "Synergy in Action – The Breathing Muscles as the 'Power Pump'"

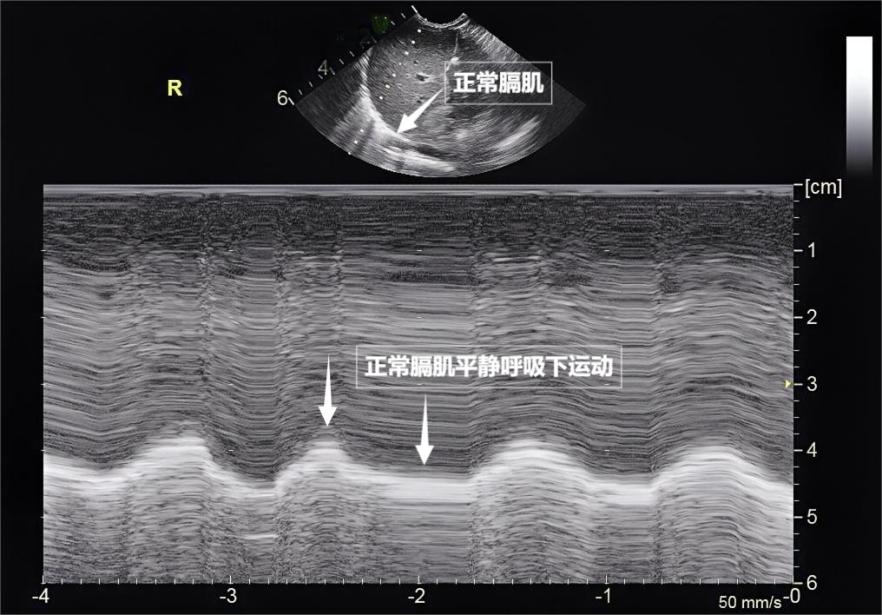

Breathing may seem simple, but it is actually a "team exercise" involving the precise coordination of multiple muscle groups. Lung ultrasound not only allows observation of lung morphology but also, through real-time dynamic imaging, "captures" the activity of these breathing muscles, providing a unique perspective for assessing respiratory function. The diaphragm is the "commander" of the breathing muscles, located between the thoracic and abdominal cavities. During quiet breathing, the diaphragm contracts and descends, expanding the thoracic cavity, naturally drawing air in; during exhalation, the diaphragm rises, and lung elasticity completes exhalation. Under ultrasound, the diaphragm appears as a smooth arc, moving up and down in a rhythmic pattern (see image below). The external intercostal muscles are the "elevators of the intercostal spaces," lifting the ribs during contraction, expanding the anteroposterior diameter of the thoracic cavity, and assisting in inhalation. This "golden duo" accounts for over 70% of the work in daily breathing, serving as the "main force" for maintaining respiratory function.

Image shows normal diaphragm ultrasound appearance

When the body needs more oxygen (such as when climbing stairs), the 斜角肌 and sternocleidomastoid muscles "reinforce." In extreme cases (such as an asthma attack), the abdominal wall muscle group and internal intercostal muscles are mobilized in emergencies.

The "scout" of lung ultrasound dynamically evaluates changes in respiratory muscles by observing the order of muscle activation, measuring diaphragm thickness and mobility, and capturing paradoxical muscle movements. It helps detect early signs of "overload operation" in the respiratory system, providing precise evidence for doctors to adjust treatment plans.